I have a photo way back on my Instagram feed of a woman in a magenta pink jacket sitting on a folding chair at the Tate Britain, her back curved with age. She was sketching a Turner, the 19th Century English painter known for turbulent marine paintings and romantic, warm watercolours. I had never seen a person set up in front of a painting like that before, studying someone else’s art with their own art supplies in a bag at their feet. It was such a quiet scene, much like The Scarlet Sunset, Turner’s 1830’s watercolour with warm reds against cool blues. I was in a photography phase, more interested in capturing life than a fixed piece of art. So I took her picture.

Last month, just over ten years later, I found myself sketching at Le Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature - the hunting and nature museum in Paris. It’s a beautiful place, two grand 17th century hotels joined together to explore the relationship between humans and the natural world. There are taxidermied wild boars, foxes and grizzly bears. Tapestries, ancient hunting paintings, still lifes of lavish tables filled with game and a handrail made of bronze feathers. There are also contemporary installations throughout the museum, like the marble-tiled room with butchered animals made from discarded textiles1 hanging from the ceiling. We the students (from the retreat I’ve written about here and here) were tasked with sketching five images that caught our eye. This explains why I was standing in front of a display case filled with ornate 18th century muskets. I have never been drawn to a gun cabinet before, but these objects were things of beauty. I was also curious about the two elderly women peering into the case beside me, chatting away in thick Brooklyn accents about everything inside.

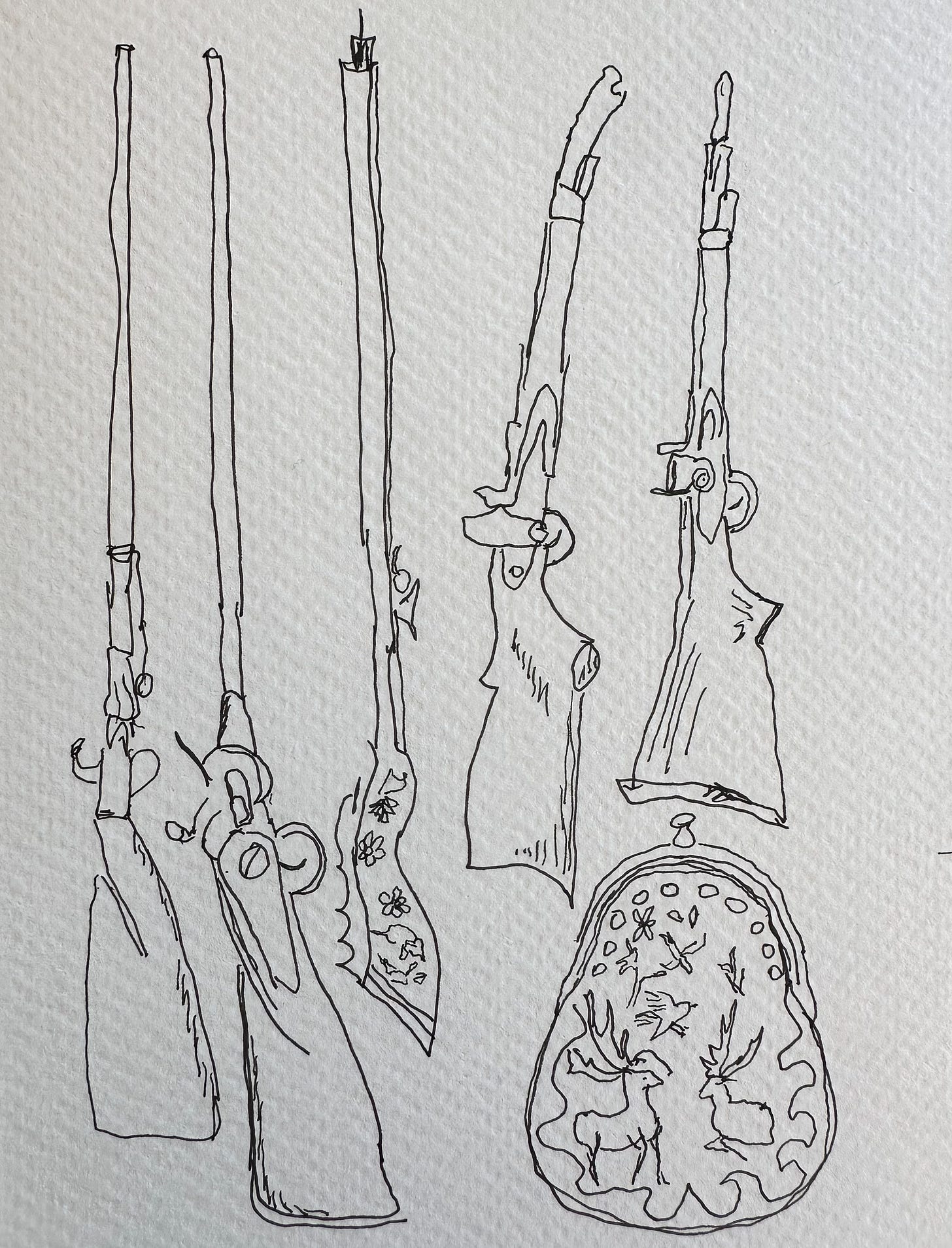

“Look at that, can you see the detail on those guns? And the silver work on the triggers! And what about that velvet pouch with the embroidered scenes all over it? There’s a dancing stag, and a swallow! Now what on earth would hunters be doing with a pouch like that?2 Where’s the information, nothing is labelled, what is going on around here?”

And off went one of the women in search of museum staff. She returned a minute later, chatting away with a man, in french.

I have been trying to learn french for many years. I can order food, chat about the weather, talk about my family, ask a few questions. I cannot inquire about the history of embroidery and the role it once played in male hunting garb. I hoped that someday I could, and I hoped that I would always be as curious as those women.

“I’ve lived here for forty years!” said the bilingual woman, now leaning over my sketch book. “Learning French took forever, but I got there.” And on we went, sharing that she and her friend were in fact from Brooklyn and have known each other since they were little. We marvelled at the hours it must have taken a team of women to embroider a man’s gunpowder pouch. That she had married a French Canadian man, and he had gone to St. Francis Xavier, the University just forty minutes from my parents’ home in Nova Scotia. That his career as a physician took them to Paris, and they had stayed here, together, until his death a few months ago. “Life’s not much fun anymore, but I’m trying my best,” she told me, tearfully, in front of shotguns inlaid with mother-of-pearl vines, flowers and tiny, dancing animals.

I thought about Frannie’s prayer in Betty Smith’s 1943 novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. “Dear God, let me be something every minute of my life. Let me be gay, let me be sad. Let me be cold, let me be warm… let me be something every blessed minute.”

“Of course I read that book, she said with a shrug. We all did.”

This is what happens when you sketch in a museum. You engage with details differently; you see and notice things in a deeper way. And people notice you too.

When it was time to go I put my supplies away and found my mother perched on a sofa upholstered in moss-green velvet, drawing a taxidermied stag.

Installation - La Chair du Monde - by Argentine-American artist Tamara Kostianovsky

The pouches, much like Scottish sporrans, were worn by hunters and used to store gun powder

Whilst I think the exhibition would have been amazing, the conversation with the woman from Brooklyn seemed filled with dimension and possibility. And that dear senior artist! I want to be like that.

Oh, I so want to be just like that. To never let go of the wonder...

This is priceless, Lindsay! As is evident in many of my essays, I am so attracted to this kind of interaction, opportunities for connection, of wonder, of just letting the moments be what they will without us feeling the need to inject ourselves in any particular way. I love that you have memorialized both the exchange with the women from Brooklyn (my in-laws are from there, too), and that quiet, powerful scene of the artist studying another artist's work. So much to take in!